Environmental Justice

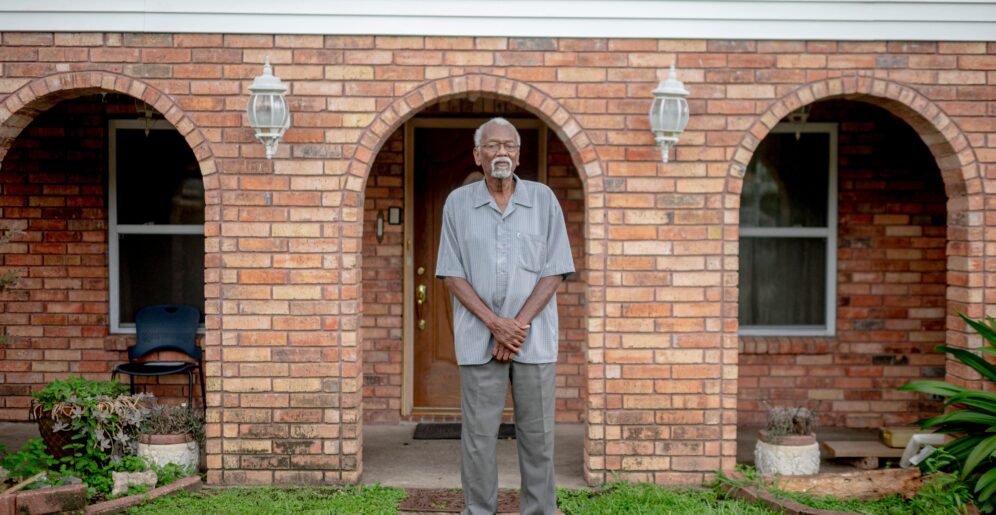

Voices From Cancer Alley: Black Families Demand Environmental Justice

Environmental racism has been a persistent issue for decades, disproportionately burdening marginalized communities with toxic air and polluted water. As environmental justice activists advocate for equity, it’s essential to examine the role of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries in this crisis.

These industries restrict access to green spaces, clean air, and safe drinking water for these communities, contributing to what’s commonly called “Cancer Alley.” This term usually refers to an 85-mile stretch between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, home to 200 petrochemical plants in a predominantly Black region along the Mississippi River. Less known is that the phrase also appeared in the early 1980s to describe areas along the New Jersey Turnpike leading into Philadelphia. A report analyzing cancer mortality data from 1950 to 1969 identified regions the EPA marked as high risk, largely due to pollution from industrial emissions, pushed many to demand answers.

Media coverage sparked a wave of studies into these concerns. A 1984 Journal of the National Cancer Institute study examined mortality data from 1968 to 1980, revealing clusters of male cancer deaths in Philadelphia neighborhoods. It found that air pollution, compounded by socioeconomic factors, shaped lung cancer patterns. That same year, National Institutes of Health researchers linked residential exposure to petroleum and chemical plant emissions with higher cancer and cardiovascular disease rates, noting strong correlations shaped by class and occupation.

As research expanded, questions emerged: Are Black communities more adversely affected than white ones? Studies indicate that, by the 1960s and 1970s many of the most polluting facilities were sited in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Journalist Antonia Juhasz, author of Black Tide: The Devastating Impact of the Gulf Oil Spill, has documented how residents of Louisiana’s Cancer Alley are exposed to some of the nation’s worst pollution. These communities face severe water contamination, while petrochemical companies drive greenhouse gas emissions and industrial air pollution at staggering levels.

History underscores the pattern. In the late 1970s, residents of Toms River, New Jersey, noticed unusually high childhood cancer rates. Investigations revealed that chemical companies had been dumping toxic waste into waterways for decades. Although lawsuits led to settlements, residents criticized the monetary compensation as inadequate and the process as lacking public input. The case spotlighted the need for systemic change. While “Cancer Alley” isn’t an official term in New Jersey, towns like Franklin and Linden remain flagged by the EPA for elevated cancer risks tied to ethylene oxide and other pollutants. Over time, New Jersey created cancer registries, launched cleanup efforts, and most recently secured a $2 billion settlement with DuPont and related companies to remediate PFAS-contaminated sites—proof that industry accountability is possible.

But why hasn’t Louisiana seen similar urgency? While New Jersey received high-profile settlements, Louisiana residents continue to fight for basic protection. When toxic chemicals surfaced in New Jersey, the media amplified public outrage. Yet many outlets have overlooked Louisiana’s environmental racism, leaving residents with little coverage and even fewer resources.

Activists have stepped in to fill the void. This led mother-daughter duo Roishetta and Kamea Ozane to travel across the world to shine a light on the “Toxic Billionaire Tour,” as they confronted the financiers of harmful natural gas projects. Roishetta, founder and director of The Vessel Project, has spoken publicly about the toll:

“The water quality is severely compromised by toxic pollution, which has devastating impacts on my family. Contaminated water leads to a range of health issues. With my own children suffering from asthma and eczema, we are constantly battling these illnesses along with the stress of knowing our environment exacerbates their conditions. We shouldn’t have to choose between clean air and water and our children’s health.”

In Cancer Alley, everyday life unfolds next to petrochemical plants. Playgrounds, schools, farms, and homes sit in the shadow of flares, plumes of black smoke, and crude oil spills that stain the ground and poison the air. Kamea, just 12 years old, has emerged as a vocal activist. She told Democracy Now:

“Citibanks keep funding these fossil fuel industries in our communities. They put them in the small Black and Indigenous communities on purpose, because they know that we can’t do anything about that. They put them in poor communities and low-income communities on purpose. This is not OK. This is racist,” she said.

The human toll is undeniable. In an interview with Democracy Now, Juhasz emphasized that pollution in these areas of Louisiana contributes to “three times the national rate for low birth weight and two-and-a-half times for preterm birth.” In 2022, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, designated the region a global “sacrifice zone,” one of the most polluted places on Earth—a site of human rights violations.

The state’s failures have only deepened these issues. The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) along with the EPA, has repeatedly fallen short of enforcing federal standards, leaving residents vulnerable to unchecked industrial pollution. Many believe this failure to uphold human rights and provide crucial information is influenced by racial factors, leaving the area with the highest cancer risks.

“There is a stark contrast in the response to health issues caused by chemical plants in communities of color versus white communities. The cases involving companies like DuPont highlight systemic disparities; when affluent areas are impacted, the response is quick and substantial. Meanwhile, we often receive scraps and are dismissed,” Roishetta told AFROPUNK.

Her demands are clear:

“I demand that they take responsibility for the harm their operations inflict on our communities. It’s not just about profits; it’s about our lives and the health of our children. I call for clear reporting on emissions and pollutants, urging them to be transparent about what they release into our air and water. I insist that they listen to us; our voices matter.”

Additionally, local activists also call for a moratorium on new fossil fuel and petrochemical plants, coupled with investments in renewable energy. Juhasz has emphasized that federal incentives like the Inflation Reduction Act already offer models for phasing out fossil fuel operations and restoring polluted lands.

The real issue is not whether Cancer Alley exists—it is how systemic racism dictates which communities receive protection and which are left behind. Addressing this crisis requires more than policy tweaks. It requires accountability, strict enforcement of laws like the Clean Air Act, and corporate investment in community-led solutions: clean water projects, health clinics, and green spaces.

Anything less allows the cycle of environmental racism to continue.

Get The Latest

Signup for the AFROPUNK newsletter