BooksListsRevolutionary

afropunk 10: revolutionary black reads

I’ve been an avid reader since the days of my toddlerhood, when mom used to put books and magazines in my playpen. I was the kid with a library card dragging home a backpack filled with sci-fi, mysteries, poetry and biographies. In high school I couldn’t play basketball, but was chosen “Biggest Reader” by the yearbook committee. While I would grow-up to become a journalist and critic, in 2018 I began writing a book column called The Blacklist for Catapult. My mission was to spotlight subjects that were less known than the regular canon; and I’ve also profiled out-of-print or forgotten Black authors for The Paris Review and Longreads. When AFROPUNK asked me to compile a list of revolutionary Black reads, I followed the same guidelines, wanting to present to the audience authors or books that were unfamiliar, but radical.

Charlotte Carter’s Walking Bones, is a chilling New York City noir novel of fatal attraction, edgy sexuality and Manhattan cool. Telling the twisted tale of a relationship between a Black former model named Nettie and her crazy relationship with Caucasian businessman Albert Press, who falls in love with her after she smashes a glass in his face. Author Carter is known for her jazz detective series featuring Nanette Hayes (Rhode Island Red), but the gloomy black cloud fiction of Walking Bones was something completely different for the author. Citing 1980s writer Nettie Jones’ erotic novel Fish Tales as inspiration, Walking Bones is a story that lingers in your mind long after you’ve finished the book.

Toni Morrison

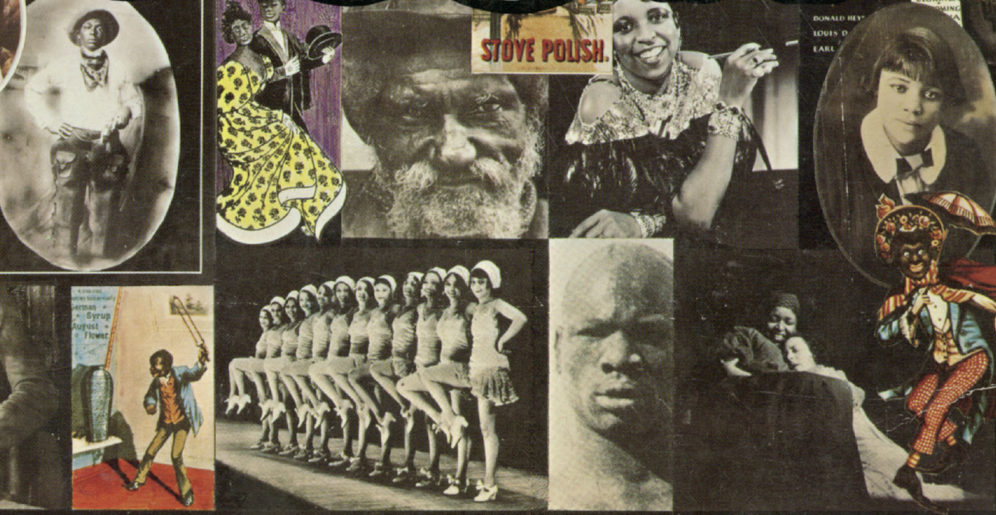

Toni Morrison is best known as the writer of literary masterworks,The Bluest Eye and Beloved, but her work as a Random House editor during the 1970s and early ‘80s should not be discounted. During her stint at the publishing company, Morrison introduced the world to numerous writers, including Gayl Jones (Corregidora), Henry Dumas (Ark of Bones and Other Stories) and Nettie Jones (Fish Tales). Still, it was the non-fiction collection she helped edit, The Black Book, that would become one of her biggest sellers. Serving as an early guide through African-American history, The Black Book was originally published in 1974. The groundbreaking book is full of photos, files and documents that NPR described as “a scrapbook to the African-American experience.”

Virtuoso writer Edward P. Jones won a Pulitzer Prize for his first and only novel, 2003’s The Known World, but he is also one of the best living short story writers in America as proven by his second collection, All Aunt Hagar’s Children (2006). The book’s fourteen stories take place in the author’s native Washington, D.C., where he still lives, and depicts the complex lives of regular folks just trying to make it through the bullshit obstacles and dire dangers of the world. Jones’ style is beautiful, lush and, as in the stand-out story “A Rich Man,” packs a novel’s worth of ideas into its short form.

Samuel R. Delany

There was a “once upon a time” when Harlem native Samuel R. Delany was the only Black (professional) science fiction writer. In addition to his own innovative novels — including Nova and the massive 1975 classic Dhalgren — he was one of Octavia Butler’s writing teachers. Although Delany has written everything from comic books to scholarly essays to prize winning short stories, it’s his moving 1988 memoir, The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village, 1957-1965, that I’ve revisited more than any the other text. Detailing his early years as a brainetic but dyslexic student at the Bronx High School of Science, then his life as a married but also gay, bohemian sci-fi writer in New York’s bohemian Greenwich Village, Delany weaves a splendid narrative that serves as the perfect introduction to his genius.

There are some who only know the late Ntozake Shange as the author behind For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf, a stage-piece that became a Tony Awards-nominated play, but she was also a respected poet and novelist who wrote in a jazzy style that could be as wild and free as a John Coltrane solo. My introduction to her work was finding the brilliant collection nappy edges (1978) on my mama’s bookcase when I was a teenager. Whether riffing about men, music or misery, Shange’s writing in Nappy Edges was quite moving and would become a major influence for many post-Black Arts Movement scribes.

bell hooks

When I was a young music critic coming of age, a friend introduced me to the work of bell hooks, and her smart, sharp and often snide writing changed the way I thought about feminist theory, personal essays and cultural criticism. Serious without being pretentious, hooks has also been quite prolific, as she turned out memoirs (Bone Black, Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life) and stellar essay collections that included the brilliant, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. In that book, hooks dived deep into the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Carrie Mae Weems and Emma Amos, and crafts a must-read text for anyone interested in Black art and artists.

Beginning in the early 1960s there was an influx of Black writers living in the Bay Area that included novelist Ishmael Reed, poet David Henderson and Al Young, who switched literary forms depending on his mood. The Mississippi native moved to Oakland in 1961, and wrote a trunk-full of poems, novels, film scripts and short stories, his style inspired by the music he loved, which included everything from Mozart to Mingus to Motown. In the 1980s, Young penned several musical memoirs including Bodies & Soul (1981), Kinds of Blue (1984) and Things Ain’t What They Used to Be (1986) that used the songs of Duke Ellington, Aretha Franklin and the Supremes, among others, to jump-start his memories. As Publishers Weekly proclaimed, “Young’s exuberant essays are imaginative and lyrical paeans to the magical powers of both language and music.”

Greg Tate

Back when alternative newspapers mattered, NYC’s Village Voice was the leader of the pack. In the 1980s, music editor Robert Christgau was determined to make the arts section diverse, and began publishing the works of still-relevant Black writers like Nelson George, Carol Cooper, Barry Michael Cooper, Joan Morgan, dream hampton and the brotha of the moment Greg Tate. Calling himself Ironman, his work was riotous like Sly Stone on speed, as Tate pioneered what we now call “hip-hop journalism,” with early pieces on De La Soul and Public Enemy, while also writing about Mile Davis, William Gibson, George Clinton and AR Kane. His first collection Flyboy in the Buttermilk serves as the perfect Yellow Brick Road to ease on into Tate’s written work. (For his music, check in on Burnt Sugar Arkestra, which played AFROPUNK Brooklyn in 2019.)

When writer Bridgett M. Davis was working on her now acclaimed memoir The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers, we spoke about the work of author Louise Meriwether, whose stirring novel Daddy Was a Number Runner served as her inspiration. Published in 1970, it is the tale of 12‐year‐old Francie Coffin who lives in 1930s Harlem amongst the tenement tribes of strugglers, hustlers and ordinary people on the verge of explosion. However, Meriwether refused for her protagonist to become a victim of ghetto misery. Fellow novelist Pauline Marshall wrote in her New York Times review, “The novel’s greatest achievement lies in the strong sense of Black life that it conveys; the vitality and force behind the despair. It celebrates the positive values of the Black experience: the tenderness and love that often underlie the abrasive surface of relationships.”

Brian Greene contributed a wonderful essay on little known novelist Robert Deane Pharr to the recently released collection, Sticking It To The Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980. Although Pharr launched his writing career as a novelist with The Book of Numbers (1969) when he was already a fifty-three-years-old, it was his autobiographical follow-up, S.R.O., that remains a favorite. A sorrowful novel that takes place at a Harlem single-room occupancy hotel, the S.R.O. was the true heart of darkness where drug addicts, drunks, whores, thieves and other losers disappeared from the world. Pharr writes about the ugly beauty of the S.R.O. with both disgust and passion.

Get The Latest

Signup for the AFROPUNK newsletter